- Home

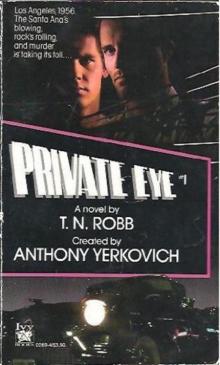

- T. N. Robb

Private Eye 1: Private Eye Page 8

Private Eye 1: Private Eye Read online

Page 8

Cleary pulled open the desk drawers, rummaged through them in the dim light. Then he tried the doors of a heavy wooden cabinet behind Schneider's desk, and found them locked.

"I'll get it," Betts offered. Pulling out a slender, hairpin-like tool from his shirt, he jimmied the lock. A moment later, he smiled up at Cleary. "Magic."

Cleary opened the cabinet door and reached inside. As he did, he knocked over a decanter of Scotch, spilling it on his pants. "Damn." He set the container upright, and brushed a hand over his pant leg. "Just a liquor cabinet."

He was about to close the door when he noticed a ledger resting upright against the cabinet wall on the left. He flicked his lighter on and began paging through it. The lighter Nick had given him. There was a certain irony about that, he thought, as he turned through several more pages.

"So we were waiting out there for the local cop to go by," Betts said as he rifled the files. "Was that it?" Cleary didn't answer.

"I guess your experience as a cop is paying off," Betts said.

When Cleary again didn't respond, he continued, "Nick told me you got a raw deal. Someone set you up on a bribery rap."

"Betts, stick to your business over there."

"All right. All right. But I don't see anything labeled 'payoffs.' What do you think it would be under?"

"Keep looking," he growled.

"Wish we could turn on the lights."

Cleary shook his head, exasperated with Betts, then leaned forward, staring at the page before him. "You read?"

Betts looked up. "Menus."

"Check this out."

Cleary handed him the ledger, opened to the page he had been studying, then flipped him the lighter. Betts turned on his reading light, and leaned close to the page.

"Hey, the Clovers never went gold with that song." He stabbed his finger at the page. "Says here they shipped half a million platters of 'Lovey Dovey,' and I know for a fact they topped out on the charts with half that."

Cleary frowned, moved up to Betts, and planted his finger on the opposite page. "Try over here. There's two pages to this menu."

"Jeez, there must be at least two hundred grand in payoffs," Betts said after a moment. He looked up, pocketing Cleary's gold lighter. "And all to our favorite radio personalities, including fifty Gs to our buddy, the Gator."

Cleary noticed a stack of cards on one corner of Schneider's desk and picked one off it. It was an unposted invitation to a party. Something about it stirred his attention, but he couldn't pinpoint it, so he pocketed the card. "Let's get out of here." He took back the ledger, ripped out the page, and returned it to the desk drawer.

"Put it back, Betts."

"Put what back?" he asked.

Cleary walked over to him and began frisking him. "Hey," Betts shrieked. "We don't know each other that well, man."

Cleary pulled the gold record out from under the back of Betts's T-shirt, and hung it on the wall again. Next to it he noticed a picture of two men; one he pegged as Schneider, the other looked like a reformed mobster.

"I don't feel like getting popped on the way home 'cause some hillbilly klepto's filling out his record collection. You got that?"

"Klepto, huh?" His body stiffened in a defensive stance, his mouth turned down angrily. "Hey, I may be a lot of things, Cleary, but a sexual pervert ain't one of 'em. You better dig that from the hip-hop if you want to keep working with me."

They left the office without another word, and were about to leave the building when Betts turned to Cleary. "And another thing. I don't jus' wanna know the name of the song, I want the lyrics, too."

"What the hell are you talking about?" Cleary asked, wondering what he was doing in the same postal zone with this preverbal delinquent.

"About what we're doing. That's what. I wanna know what's going on."

"All right." He motioned toward the door. "Out."

It was dawn as they drove away from the Starlite Building, and traffic was just starting to pick up. Betts looked expectantly at Cleary. "Well, man, speak up."

"About what?"

Betts folded his arms and stared out the window, irked by Cleary's strong, silent-guy game.

"Okay, Betts," Cleary began. "Get ready for a few lines of lyrics. Before Williams got knocked off, he was about to spill his guts to a federal task force about the Mafia's attempt to control the record biz through payola schemes. Mickey Schneider had everything to lose if he talked."

Betts nodded, pleased that Cleary was taking him into his confidence.

"Now here's something for you to think about. Both Nick's office and my apartment were tossed after Nick was killed. Whoever the guys in the Packard were, they didn't get all they wanted when they got the tapes."

Betts shrugged. "Maybe Nick didn't hand over both sets."

"There was more than one?"

He nodded as they turned on Sunset. "I'm sure he made duplicates, for insurance I s'pose, though it beats me where he would've stashed 'em."

"That's it," Cleary said softly, hitting the heel of his hand against the steering wheel. Several blocks slipped by as he mulled over what to do next.

"You can drop me right on the corner. I've got the Merc in the body shop down the block. Trying out a new color after our little run the other night."

"I think you better park it a while. You need more than a paint job to hide that thing."

"It's my wheels, man."

"It's your ass, too." Cleary pulled to the curb. "I've got something to keep you occupied."

"Yeah, what?" Betts asked suspiciously, the long hours starting to show in his impatience.

"I want you to pay Schneider a visit."

"And say what? 'I like your gold records'?"

"Tell him you were with Nick the night he got hit. Tell him you've got the Buddy Williams tapes."

"That's gonna make me a real popular boy. I like it. Want me to quote a figure on the tapes?"

"Ask for ten grand."

"Nice round figure." Betts placed his hand on the door handle.

"By the way, where'd you learn to pick locks like that?"

"Home-study course." He grinned and pushed open the door. "See you later, C-man."

Cleary drove off, feeling as if the night's work had been productive. Schneider was definitely in deep, but was he the end of the trail? He slowed for a traffic light, and as he came to a stop, remembered the invitation he had taken from Schneider's desk. He pulled it out of his coat pocket, and reread it.

Starlite Records requests the pleasure of your

company in honor of their newest recording artist,

Eddie Burnett.

The last line announced that the party would be held at the residence of Eddie Rosen. Cleary stared at the name. Something about it bothered him. He didn't know the man, but knew he didn't like him. He wanted to find out what Rosen's connection was with Schneider and Starlite. He pocketed the invitation as the light changed.

Cleary drove on, but when he reached the turnoff for St. Ives, he kept going. He headed out of town, intent on taking a look at Rosen's house. But somewhere en route his mind drifted from lack of sleep. He made a wrong turn and didn't realize it, not until he reached a familiar street. He couldn't believe it. His mind had gone on automatic, and he had been drawn like a magnet to his old house in the suburbs, to Ellen.

In the pale morning light, the place looked smaller than he remembered—a pale yellow concrete house set back in a thicket of trees. Ellen had landscaped the yard with hedges and cactuses and wildflowers. And for a long time, it had been their private Eden, a world sliced away from his life on the streets. And then he had blown it.

He parked parallel to the edge of the yard and got out of the Eldorado. He strolled up the walk, remembering other mornings when he had done exactly this, mornings after working around the clock, when he was so beat he could barely see straight. He had unlocked the door and stepped into the silent house, embracing its warmth and the faint fragrance of Ellen's perfume that lingere

d in the air like the scent of fresh flowers. The first thing he had done was shower, scrubbing away the vestiges of the L.A. streets. And then he had slipped into the bedroom, into Ellen's arms.

Gone, buddy. All of it down the tubes.

He rang the doorbell. When she didn't answer, he knocked and rang the bell again and again. As the door finally opened, his heart flopped in his chest, and then there she was, standing there in a short terry-cloth robe, her black hair tangled, her eyes puffy from sleep. She just gazed at him for a long moment, a hand holding the throat of the robe closed, as if she expected him to rip it away.

"You gotta be drunk to be here. Right? You're drunk, aren't you, Jack? I can smell it on you." She started to slam the door, but his shoe jutted out, wedged between the door and the jamb.

"I'm not drunk, Ellen. I just want to talk to you." He pushed the door open.

She stood slightly behind it, her dark eyes glossy with anger—and perhaps a bit of fear, as well. She ran her fingers through her hair, combing it back. "Make it snappy."

"Thanks for coming to Nick's funeral."

The anger immediately bled out of her face. "Oh, God," she whispered. "I'm sorry about Nick. I really am. I—I wanted to say something to you that day, but..."

"But you were with some other guy. Some cowboy actor, right?"

Now why the hell had he said that? The anger leaped back into her eyes. "So what about it?"

"Who is he?"

"A friend of mine."

"A lover, you mean."

She didn't answer.

Cleary, his voice harder, insistent, a voice that demanded an answer, said, "A lover. Right? Does he wear his spurs to bed, Ellen?"

"Jack, correct me if I'm wrong, but we're separated, right? You were drunk, remember? You got suspended from your job, and for weeks you made my life a hell. I put up with all of it until you hit me. Now if you don't mind, I'd like to go back to bed."

He dry-washed his face with his hands. "I'm sorry, I didn't mean—"

"You never do," she snapped. "You always mean so well, don't you, Jack? But then you somehow have this way of twisting things, making things so—so ugly."

Was it true?

Was he the sort of man who ranted and raged and then apologized later? When he was sober? You were worse, buddy. Much worse. "Look couldn't we have coffee or lunch or something, Ellen? Couldn't we at least try to—"

"No. You had plenty of chances, Jack. We tried, and nothing worked. Now please. Just go. Don't make me call the cops. I really don't want to. But if you don't leave, I will. I swear I will."

Cleary slid his foot out of the door. He reached out and touched the back of his hand to her face. Then he turned and moved back down the walk, an ache wider than the Pacific tearing open inside him. Call me back, Ellen. C'mon. Please, say, "Hey, Jack, hold on." C'mon, just say it.

But she didn't. He heard the door closing, softly.

She's nice enough and she's sure a looker, Jack, but I don't know, man, I think she's gonna break your heart, Nick had once said to him shortly after Cleary and Ellen had gotten married.

Break your heart. Yeah, you bet. Too bad it turned out to be true.

His legs felt wooden as he started back down the walk. He heard the whisper of his own footfalls against the concrete, whispers like a small, lost voice, the voice of the man he had been.

Somewhere distant, a bird warbled in the stillness, as if willing him to glance back. He did. And there, silhouetted in the bedroom window, was a man, watching him. He knew, without knowing how he knew, that it was the actor.

TWELVE

Studio Work

"Mr. Schneider, please," Johnny Betts said in his most polite, adult tone to the secretary who answered the telephone at Starlite Records.

He was at a phone booth just three blocks away from the record company, and figured Mickey Schneider would quickly fit him into his schedule when he heard what the call was about.

"Mr. Schneider is going to be busy all day at a recording session. Can I take a message?"

"Yes. Ah, I mean, no," Betts stuttered. "Maybe you can help me. I'm supposed to fill in for the recording engineer. But I didn't get the address of the studio."

"Well, you certainly shouldn't be bothering Mr. Schneider about that. I'll tell you where it is."

Betts jotted the address on the inside of the phone booth as she gave it to him. "Thanks. You're a doll. I just hit the buzzer to get in, right?"

"If the band's practicing, you might not be heard for a while. It's better to go around to the side, and press the lever just over the door and let yourself in." Now why couldn't all secretaries be so helpful? he thought with a smile. Then he hung up and started thumbing a ride to the studio. He had conceded that Cleary was probably right about the Mercury. Even with a new color, the cops might still recognize it.

A half hour later, Betts was leaning against the wall in the corner of the recording studio, looking passive and indifferent. But inside he was revved. What luck, what hot damn luck. Eddie Burnett, the numero uno ticket in town, was right here cutting a new tune.

This was something he could tell his kids about. His grandkids. It would become one of those stories the family passed down from generation to generation. Your grandpa Betts was there the day Eddie Burnett recorded "Sunset Strip." He even talked to him, got to know him. They were buddies back then. Grandpa Betts even got in a lick or two with the band from time to time.

Eddie struck the first chord of the song, played a couple of bars, then stopped. He leaned over to the stand-up bass player, told him the chord change. He counted to three, and they hit it again.

Betts glanced across the studio at Schneider, who was fidgeting about next to a blonde half his age. It was obvious he didn't have a clue to what was happening onstage, but he could smell money in the making. Schneider, he figured, was the type that would applaud someone farting if he could make a fast buck on it.

He turned back to the band. Cleary would be blowing a fuse if he knew he was more interested in Burnett than Schneider. But when it came to music Cleary was like Nick; he was deaf. The sounds that made his soul sing, that made the world something more than the usual drag, were just noise to people like Cleary who didn't know how to listen, who didn't feel it. But there wasn't another place he would rather be right now. Rock and roll was a tidal wave, and Eddie B. was ridin' high. He would just take his time getting around to talkin' to Schneider, because once he laid his rap on him, there was no more hangin' out here.

After a few bars of the song, Burnett signaled the band to stop again. Schneider stood up and took a couple of steps toward Burnett to find out if he liked what he had been hearing.

"What d'ya think, Eddie?"

"It's not working."

"'It's not working,"' Schneider said, throwing up his hands. "The damn thing doesn't work!"

Betts knew that for Burnett, this was just part of getting the tune right, but Schneider looked like he was on the edge of despair. He was just probably thinking Burnett was about to throw in the towel, to him the song was "broke." That would be the end of it. Schneider wouldn't have a clue how to fix it.

He turned to his girlfriend, a store-bought blonde who affected a Monroe look. She was sitting on a high stool, her legs crossed at the knees, filing her red-painted nails. "What's wrong with it?" he asked her.

"I like it," she replied, without glancing up from her nails.

"Hey, just fix your goddamn nails, will you please? And keep your mouth shut. This is a professional recording studio, got that?"

She shrugged, and kept filing.

"Whyn't you try the chord change like on 'Locomotive'?" Betts asked.

"Oh, here's another freaking country heard from," Schneider snapped, then looked to Burnett to see his reaction.

"That could work," Eddie said, nodding thoughtfully. "Damn, it just might."

"Yeah? You think it can?" Schneider gushed. Then he took Betts's suggestion as his own. "See, I'm wondering if that cou

ld be it. You know, I think it might now that I think about it. Kind of like 'Locomotive.'"

No one's gonna believe this, Betts thought. No one was going to believe that he, Johnny Betts, had told Eddie Burnett the chord change he needed to make "Sunset Strip" work. Not even his grandkids would swallow that.

Schneider, a wide smile on his face, moved over to Betts, and pointed at him. "Where do I know you from? You're with... Who the hell are you with now? It's right on the tip of my tongue."

"Me, myself, and I."

As quickly as Schneider turned on, he turned off. "Uh-huh. I'll tell you we're a little busy here right now. You better move on."

"I've got a demo I think you'll be interested in, Mr. Schneider."

"See, we really aren't signing anybody new this week. Got that?"

"You don't want to miss this one, Mickey. It's called 'Buddy Williams Live at Home.' It's his final performances. Got that?''

Schneider frowned at Betts, then looked around as if he were missing something. He crooked a finger at Betts. "You follow me."

He led him into a recording booth. He stabbed a thumb over his shoulder and told the recording engineer seated at the console to get out.

The man tapped his watch. "Studio time, Mickey. The clock doesn't stop."

"Right, get out of here."

The engineer shook his head, and walked out. I guess I really am replacing the engineer, Betts thought, and smiled to himself at the irony. Schneider checked to make sure all the mikes were off, then turned to Betts, who was casually tapping a Lucky against Cleary's gold lighter.

"I don't know what you're talking about, kid. What's this all about?"

Betts swept his arm out, indicating his surroundings. "Nice of you to take all the time and trouble, Mickey. Mighty nice of you."

"I'm not kidding, wise guy. You tell whoever sent you over here I got zero exposure in the Buddy Williams hit. You got that straight?"

"Fine. I thought you were a music lover, thought you'd appreciate having a chance to hear Williams's tunes." Betts started toward the door.

Private Eye 3 - Flip Side

Private Eye 3 - Flip Side Private Eye 1: Private Eye

Private Eye 1: Private Eye